Climate proofing portfolios is complex, but is doable and necessary. Banks who transition now towards environmental sustainability and climate neutrality will be the banks of the future.

There is little time left to do things right: it is now or never. Climate change and other environmental risks (such as biodiversity loss) now finally feature at the top of the global risks agenda (World Economic Forum, 2020). Previously, climate change seemed to be far away behind the typical time horizons of the business and investment cycle, also known as the “tragedy of horizons”. Now, the impact of climate change is right in our face and in a big way, threatening the financial system at large if not managed and mitigated.

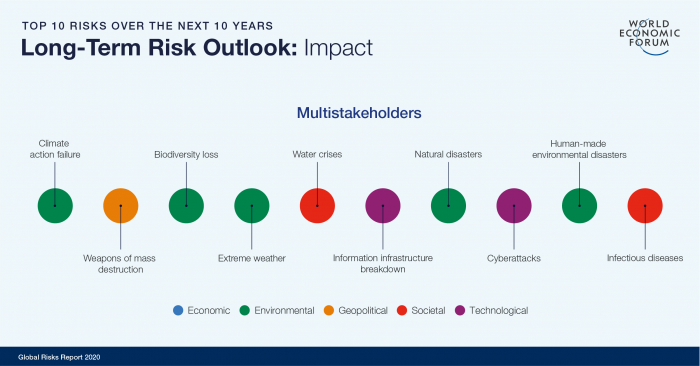

Based on the figure below and for the first time in the history of the global survey by the World Economic Forum, environmental threats dominate the top five long-term risks by likelihood and occupy three of the top five spots by impact. The principal cause of their rise is climate change.

Responses by the financial sector have been mixed. Despite the threat of climate change, 33 global banks still financed $1.9 trillion in new fossil fuel projects since the Paris Climate Agreement. On the other hand, 21 of those banks are now limiting financing for new coal projects. Other positive developments included emerging new regulatory frameworks, such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures spearheaded in its initial phase by the 16 global banks, and the Alliance for Financial Inclusion focus on inclusive green finance, also adopted by the Bank of Uganda (AFI member).

Climate change is not all gloom and doom. Climate change adaptation is also presented as the “biggest investment opportunity of this generation” (UNEP). In other words, the money and capital markets should pursue investments which no longer contribute to climate change and allow businesses to adapt to climate change, even if they are less profitable.

The financial sector in Africa has been comparatively slow to act on climate change because bankers, as well as international donors who provide financial assistance to this sector, still underestimate the impact of climate change on their business. This situation is true even though Africa is already one of the continents hardest hit by the climate change and is predicted to lose 2% to 4% of its GDP annually by 2040. Uganda is no exception; annual costs could range between USD 3.2 to 5.9 billion within a decade, with the biggest impacts on water, followed by energy, agriculture, and infrastructure.

So how can banks in Uganda adapt to this risk and take advantage of new business opportunities? Two imperatives should be pursued. First, banks should choose investing in sustainable and inclusive green growth projects and second, avoid investing in projects with significant contribution to climate change, e.g. no more fossil fuel projects, or projects leading to deforestation such as oil palm plantations by clearing virgin forest. These two imperatives can be integrated in the bank’s existing environmental, social and governance (ESG) frameworks by developing guidelines and tools to assess climate risk, take zero-emissions into investment decision-making, and provide clients with nature-based climate change adaptation options.

Over the years, most banks have adopted policies which assess risk of their loans for negative impacts on the ESG. These policies are not only adopted for moral reasons, but they also make more business sense in addition to avoiding reputational risk.

For example, if a bank provides credit to an environmentally-polluting business, there is the risk that the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) will penalize the business, which will then redirect its valuable cash flows for cleanup costs and operations. The business may end up having difficulties repaying the loan and the bank may need to restructure the loan, reducing the loan’s profitability. If the bank has initially considered the environmental risk, it would probably have refrained from providing the loan.

The same logic applies to climate risks. When a bank is aware of the climate risks, applications can be screened for these risks during the due diligence process. Ignoring climate risks won’t make them disappear. It is therefore more prudent for the Ugandan banks to address this issue.

Of course, there are costs associated in mitigating climate risk. ESG policies need to be adapted, investment officers need to be trained, and metrics must be collected and monitored. Businesses will also face additional costs to climate proof their operations. For example, in the case of agriculture, businesses need to train their extension services staff and outgrowers and conduct ground works such as digging rain infiltration ditches and establishing irrigation systems.

Becoming climate proof will be a complex process. How can banks convince their existing clients to change and become climate proof without potentially losing a customer? On the other hand, do you as a bank really want to keep customers who might default on their loan? Many climate-adaptation investments are for the long-term or beyond the maturity of a typical loan portfolio.

Irrigation Example: |

Luckily, the process of becoming climate proof can be broken down into simple steps.

The first step is to analyze and assess your portfolio exposure to climate risk. Within the current practices of banks, you would assess your clients’ performance. You need to know how much businesses are being affected by climate change “symptoms”: drought, floods, shorter or longer rains, drying of local water sources, shifting of growing seasons, and losses in land productivity.

A simple set of questions to your clients can help you assess how many of your customers are already feeling the negative impact of climate change. Is your business being affected by climate change and do you know what to do about it? In this case, the bank could help the business get an additional loan from climate-proofing investments. More worrying is when businesses tell that they are affected by climate change, but do not know what to do about it. This either requires additional technical assistance, significant risk adjustments, or not continuing further business with a client.

The second step consists of financial analysis, including a cost-benefit analysis which compares the business as usual (BAU) with the climate-proofing scenario. In the BAU scenario, no investments are done to mitigate the climate risks while the other scenario does. There will be a tradeoff between the two scenarios: and often the climate-proof scenario wins in long term.

In addition, a bank will have to decide to adopt technical and/or nature-based solutions to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Nature-based climate solutions, such as conserving the water table through forest protection harness the ecosystem services which protects against climate change. Nature-based climate solutions are more efficient and effective in the long run and do not require much involvement after the initial investment (such as establishing a forestry project).

A transition to a new low carbon economy is ongoing and imminent across the world, including in Uganda. Leading banks who tackle their climate change risks proactively will grab the many opportunities this transition provides. Fortunately, the know-how and expertise to make this a reality exists.

For further information please contact Juraj Ujhazy, team leader of the KfW / EADB Biodiversity Investment Fund (Juraj.Ujhazy [at] afci.de) or Miguel Leal, Senior Climate Change Advisor (miguel.leal [at] climatesmart.nl).