Why SME-finance?

All market economies pin their hopes on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as engine for job growth and wealth creation. The SME sector is regularly more flexible and more resilient than other sectors of the economy, and it bounces back faster after ‘shocks’ such as the COVID19-pandemic.

Yet, SMEs regularly have excessive difficulty to access credit to smoothen their operations and to invest in expansion. More specifically, the literature suggests there is a ‘missing middle-phenomenon’ in access to finance: Micro-enterprises are provided loans by microfinance institutions (MFIs), and established corporations are provided large credit facilities by banks. However, few financial institutions anywhere in the world deliberately target SMEs.

Challenges of SME-finance in Ethiopia

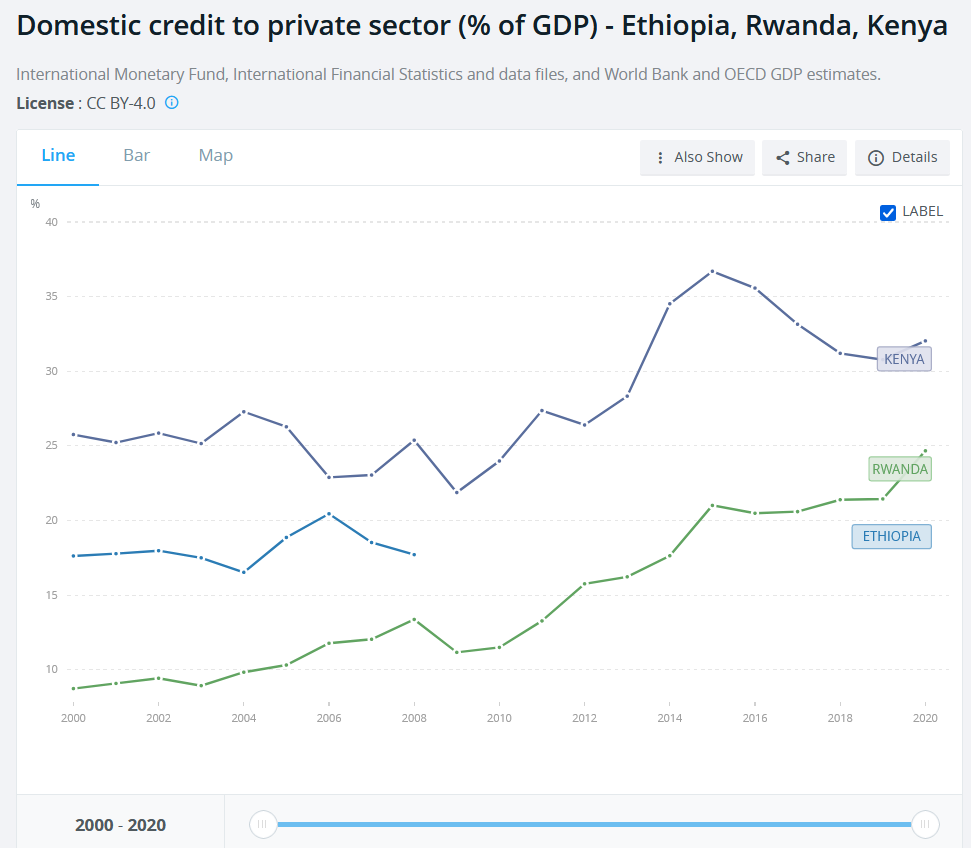

This is particularly true in Ethiopia. Because of its unique path of (economic) development (see box), Ethiopia’s financial sector is credit constraint, and thus it is a ‘sellers’ market’. Banks can pick the least risky and the most profitable among the credit applications, and those are rarely from SMEs. That could be because SME appraisal is more complicated than other borrower classes. However even simple credit products such as overdraft facilities are practically not available, found a recent study.

The study suggests that the challenge on the supply side of Ethiopia’s financial sector is deeper than just being risk-averse and profit-oriented. Anyways, Ethiopia’s financial sector is dominated by publicly owned MFIs on the one hand and by publicly owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) on the other hand. Thus, one would not expect risk concerns or profit-orientation to be the major drivers.

The deeper problem is that the financial sector operates with very low incentives to innovate because competition is low. When private banks joined the market at the turn of the century, they brought an improvement of service quality, particularly in regard of payments, and they lead in internet banking. Indeed, SMEs surveyed shared that they opened accounts in private banks for those reasons, even though most of them maintain their account at CBE.

“We would like to sell our product [peanut butter] through supermarkets but they only want to buy on credit. We cannot afford to wait for the payment for 90 days,because we have to pay our suppliers as well.”

(SME from Addis Ababa)

As all banks in Ethiopia are owned nationally so far, decreed by the law, there is both scarcity of capital to invest in new products and services, in new digital infrastructure, and in according human resources. That scarcity also constitutes a convenient barrier to international competition. This is different from all other financial sectors in East Africa where we see many banks and MFIs from West and South Africa as well as from other regions operating. Examples are Standard Bank (South Africa), Access Bank (West Africa), Bank of Africa (West Africa, itself subsidiary of a Morocco-based corporation), FINCA (US-based MFI). Furthermore, East African Banks – e. g. KCB, Equity Bank – operate in several East African countries. One of the few international NGOs that set up an MFI in Ethiopia is VisionFund.

Initiatives and opportunities to overcome barriers to SME-finance

The government of Ethiopia has pushed for reforms to address the constraint. For instance, it created a credit reference bureau and a movable collateral registry. Furthermore, a warehouse receipt system for agricultural commodities was created, which should help SMEs that trade (and export) as well as those that agro-process.

However, banks have so far made little efforts to take advantage of these opportunities. Take the movable collateral registry: The study team, interviewing among others NBE, found that banks were slow to take it up. Hence, NBE obliged them to lend at least 5% of their portfolios against movable collateral. But most banks either ‘dodge’ and just declare their existing vehicle loan portfolios, or they use the ‘back door’ of the regulation and wholesale lend to MFIs. As discussed above, this is hardly helping SMEs. There are some efforts to help MFIs lend to SMEs, by donors such as e. g. MasterCard Foundation (in a project linking Bank of Abyssinia to 4 private MFIs). World Bank, with subsequent co-funding of other international development partners (UK, Canada, Italy, Japan), set up the largest programmes that built capacity of banks and MFIs to provide SME finance.

“Repayment is quarterly, but our cash flow only allows to make repayment every six months. The nature of the business is that we buy and store required inventory for the year, or at least buy to fulfil six months’ demand, not to fail on orders. Once we miss order, it will result in cancellation and it is difficult to get the customer back.” [SME from Oromia]

Drawing on these building blocks, most banks and MFIs still have to make a strategic choice to allocate resources to their SME-finance operations. The feedback from SMEs from the study is clear: They need credit that aligns its repayment schedules with their cash flows, and that accepts the collateral that their enterprises have – stock, machinery, maybe vehicles – rather than built property. They also require liquidity-smoothening instruments like overdraft facilities or factoring.

Reference:

Deutsche Gesellschaft f. Internat. Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), 2022: ‘Barriers to Finance for Agri-SMEs in Ethiopia – desk and field research’, Addis Ababa.

Further details on the study are also given in our AFC Wordlwide 2022.

For more information, please contact: Oliver.Schmidt [at] afci.de